6 STEAM: orchestrated by a teacher

In this chapter you learn about:

What is the roles of a teacher in implementing STEAM?

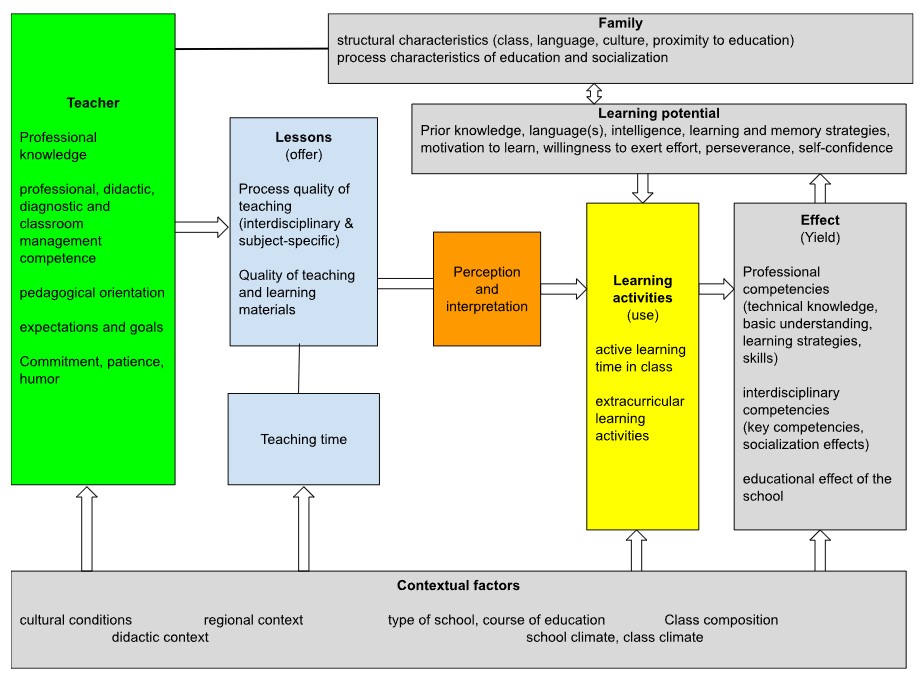

Teachers’ professional knowledge, competencies, lessons, teaching time, family, learning potential, learning activities and contextual factors influence each other and can be modelled in the following model (Figure 1) by A. Helmke (2009):

Figure 1. Model of factors and actors in education proposed by A. Helmke (2007).

In the further course of the chapter you will successively get to know the areas and examples that will concretise the model above (figure 1). STEAM activities are orchestrated by a teacher. The outcomes of the actions are influenced by teachers’ basic attitudes, coaching skills, goal setting skills, and promoting self-management. These factors are mostly important aspects of teacher education (pre-service and in-service).

Therefore, the “Teacher” aspect in the model is referring to the competences and personality of the teacher, who is influencing the lessons and in that way the process of learning. These competences include different topics. Didactic and diagnostic competences of the teacher are therefore as important as the aspect of how the teacher is leading their class. The teacher should also have a certain knowledge about the subject, that he or she is teaching his or her class, as well as educational or pedagogical positions, expectations and goals. Referring to the personality of teachers, there are also some traits that can affect the outcoming of the lessons. These traits include, for example, the engagement or motivation of the teacher, patience and humour.

The aspect “Lessons” is putting the focus on the lesson itself as a kind of offer for the children. It is affected by the competences and personality of the teacher as well as the context of the situation (type of school, combination of children, cultural and regional framework). In the lesson itself, there are some conditions, which can, in relation to the whole model, influence the outcome of the learning-process. Lessons in the model are divided into two parts: the quality of the learning process and the teaching time. It means that the lesson itself can also be extensive, so that the current topic can be found in other subjects as well. Another important matter is the quality of the material and media, the content, which is used in the lesson.

The aspect of the lesson itself, which was described before, can be interpreted by the children in different variations. It is, as already said, an offer for the students and they can make various use of it. There are activities in the actual time for learning that can be used differently. But the students can also learn in out-of-school activities.

Here we can see the effects or learning that a student can make in a lesson. But, the skills that he or she is developing, are evolving over a longer period of time. The competences that can be learned are interdisciplinary but also subject-specific. They include specific knowledge, strategies of learning, and attainments. Another aspect, which can be found here, is the educational or instructional impact of the school itself. Therefore, the school and the teachers also have the task to educate the children to be responsible humans.

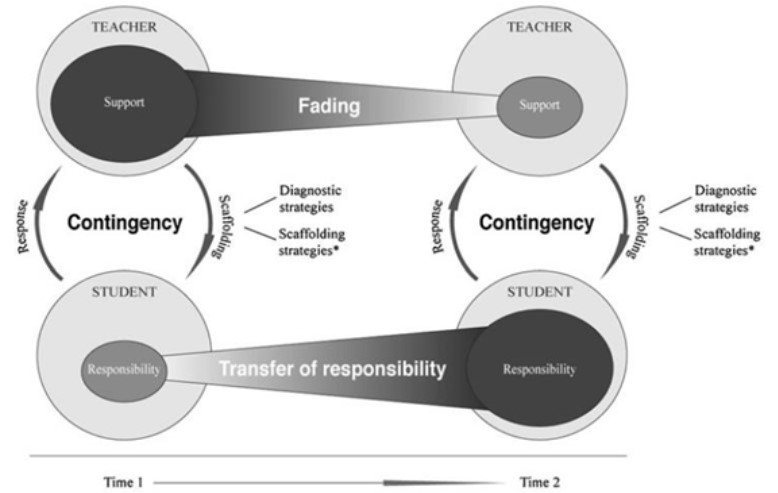

Individuals who collaborate

Scaffolding describes the process of the student earning responsibility in his or her learning process. As the teacher’s support is fading, the responsibility of the student increases. But the transfer of responsibility can only happen through specific strategies of scaffolding. They include diagnostic strategies as well, because the teacher has to determine the conditions of the learning process as well as the earnings of it regularly. With the scaffolding strategies the teacher uses, he or she helps the student in order to provide learning strategies that the child can use independently later on. In a context of contingency, the student is also giving a kind of response to the teacher. A cycle of mutual interaction is created with the focus placed on the amount of responsibility of the student (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Model for scaffolding (van de Pol et al. 2010, p. 274)

References

Hilbert, M., & Terhart, E. (2007). Guter Unterricht–Nur ein Angebot? Interview mit dem Unterrichtsforscher Andreas Helmke (= Friedrich Jahresheft). unterrichtsdiagnostik.info [PDF])

Van de Pol, J., Volman, M., & Beishuizen, J. (2010). Scaffolding in teacher–student interaction: A decade of research. Educational Psychology Review, 22(3), 271–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9127-6